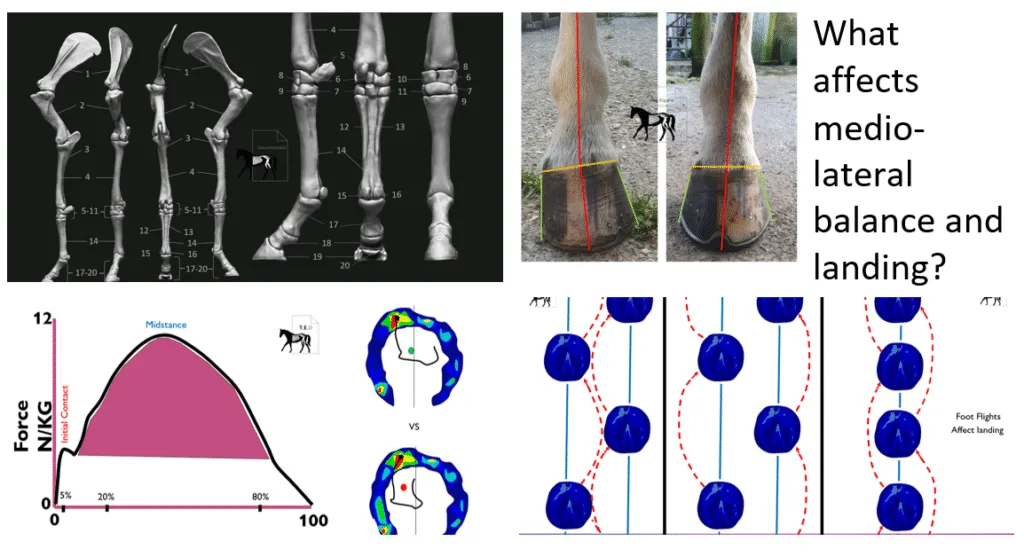

How a horse lands is recognised as a factor in lameness and predisposition to pathology, such as side bone or collateral ligament damage. This has caused the farriery industry to focus its understanding of medio-lateral hoof balance on watching horses walk, filming in slow motion, and seeing which part of the hoof comes into contact with the ground first. Then, making what they deem necessary changes to create a level hoof landing.

There is a serious problem with this historical practice, considering modern research. Let’s explore!

To understand what affects medio-lateral balance, we must outline the forces at play in the medio-lateral plane and how they change hoof shape and morphology. Then we must understand how much influence the farrier has on landing over other variables such as conformation and muscular physiology on dynamic posture.

Physics of medio-lateral balance

The physics affecting dorso-palmar/plantar balance have been discussed in depth in other articles, the hoof exceeding its elastic modulus due to reduced function and gravity. With medio-lateral balance, there are additional phenomena that play a significant role in morphological changes in the medio-lateral plane.

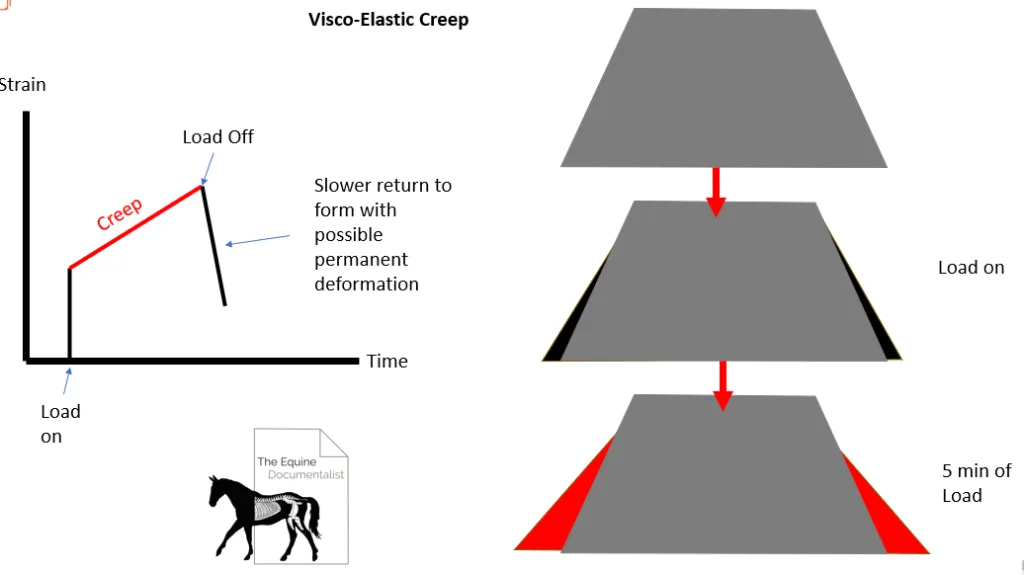

When we look at longer loading times or even cumulative short loading times, both affecting pressures experienced by the hoof over time, we start to see the effects of a phenomenon called ‘creep’. There is little research into creep in the hoof, but it applies to all Hookean and viscoelastic materials.

Purely elastic materials don’t lose any energy between the molecules after loading, but viscoelastic materials, because of the viscous part, have some rearrangement of the molecules, especially when they go outside of their elastic limit. Creep is a time-dependent deformation; it is the tendency of a solid material to move or migrate slowly or deform permanently under the influence of persistent mechanical stresses. It can occur because of long-term exposure to high levels of stress, even if they are below the yield strength of the material (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Showing how due to creep, a hoof that displaces under load will continue to displace under the same amount of load over time.

The rate of deformation will be a function of the hoofs individual properties, or composition if you like, exposure time, and the applied structural load, and hydration level will also play a vital role as the hoof becomes less stiff with increased moisture content.

As shown in Figure 4, when the hoof is loaded, we have an initial strain in response. As the load is maintained, the hoof is slowly continuing to increase in strain until the load is removed. Depending on the material properties of the hoof, we will have different rates of return to form, and some will never return to where they were, but have a certain amount of plastic deformation. This continues in cycles with the hoof always being under some kind of load.

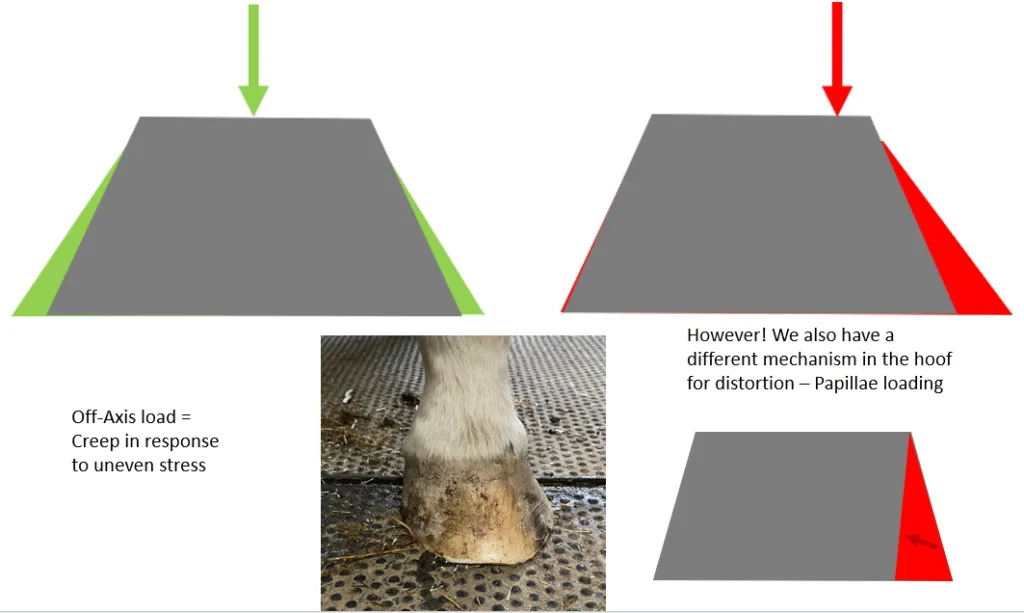

If we have off-axis load, the hoof becomes subject to the forces arising from the physiological state of the animal and the forces coming from above and the ground, be that conformation or posture, this creates a creep effect (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Central load on the hoof creates even deformation, off-axis load creates uneven deformation. Theoretically, the loaded side should deform away from the load; however, in the hoof, we find it contracts.

When we have off-axis loading, the theory would suggest increased deformation away from the load, like the top right image, the hoof creeps in the direction of increased load. However, in the hoof as a living structure, we have biological compensations that cause the loaded side to contract with increased load.

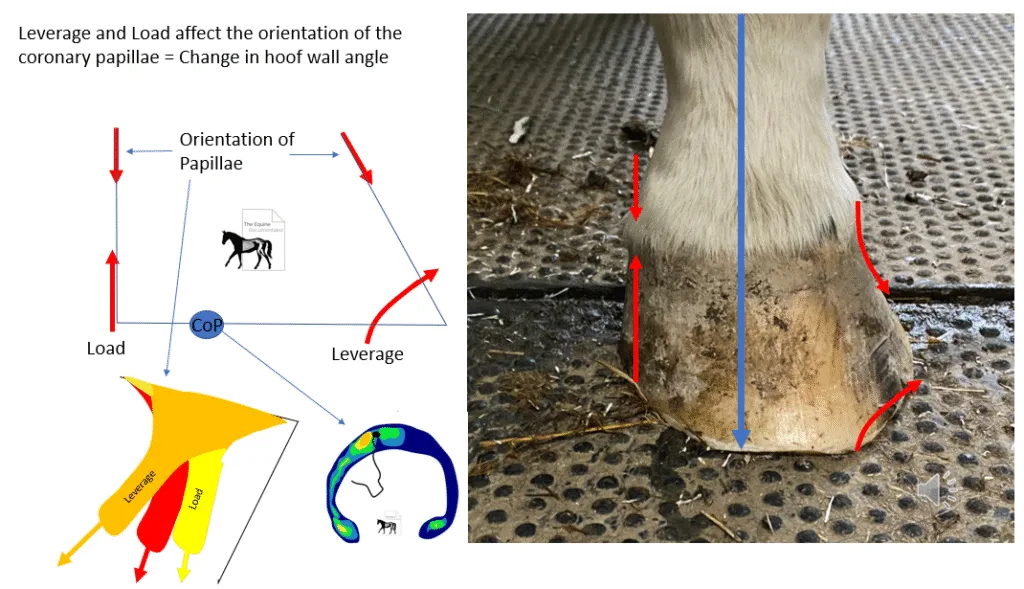

The hoof anatomy has a smart response to increased load. For the hoof wall to cope with increased load and not fail, the hoof seeks to create more vertical horn tubules, as in this orientation, the hoof wall is more adapted to compression. It does this by literally changing the orientation of the papillae the hoof grows from (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The off-axis load from the horse above creates a shift of the centre of pressure (CoP) and impulse experienced by the hoof toward the loaded side. The papillae on this side will become more upright. The opposing side experiences leverage, and the papillae become more acutely angled. This impulse creates the wry hoof seen in the image.

As farriers, we have some influence on the load experienced on the hoof, and certainly on the position of the centre of pressure (CoP), which is a calculation of the total sum of the ground reaction forces. It is movable according to hoof growth, imbalances of the foot, and angular limb deviations (Wilson et al., Oosternick et al, 2015) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The CoP is calculated from the sum of the ground reaction forces and is the action point, often called the point of force, of the ground reaction forces (GRFs).

The more centralised the cop (at midstance), the more evenly distributed the load is, meaning any part of the hoof is less likely to suffer from deformation according to the phenomena we have discussed. Farriery should understand the position of the CoP throughout the stance phase to understand the accumulative loads/impulses experienced by the hoof. The important question is, which part/parts of the stance phase?

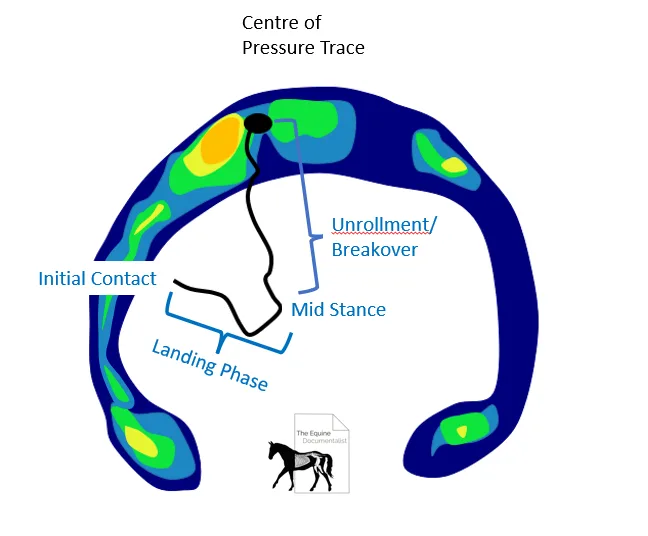

Pressure mat readings allow researchers to trace the CoP during the stance (figure 5).

Figure 5. Most common CoP trace according to van Heel et al. The black line shows the position of the CoP from landing to mid-stance to breakover. This hoof landed on the left side, the CoP moved toward the centre for mid-stance, then moves toward the toe as breakover begins.

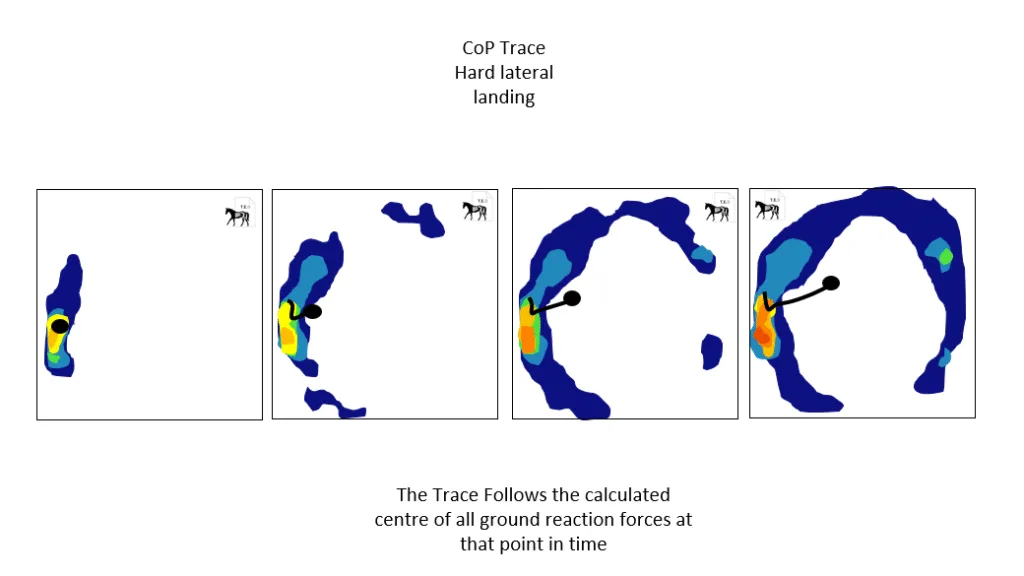

The CoP trace follows the calculated action force of the GRFs during the stance phase, giving an indication of what part of the foot was loaded throughout the stance phase (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Showing the CoP trace moving as the GRFs distribute over the foot during the landing phase.

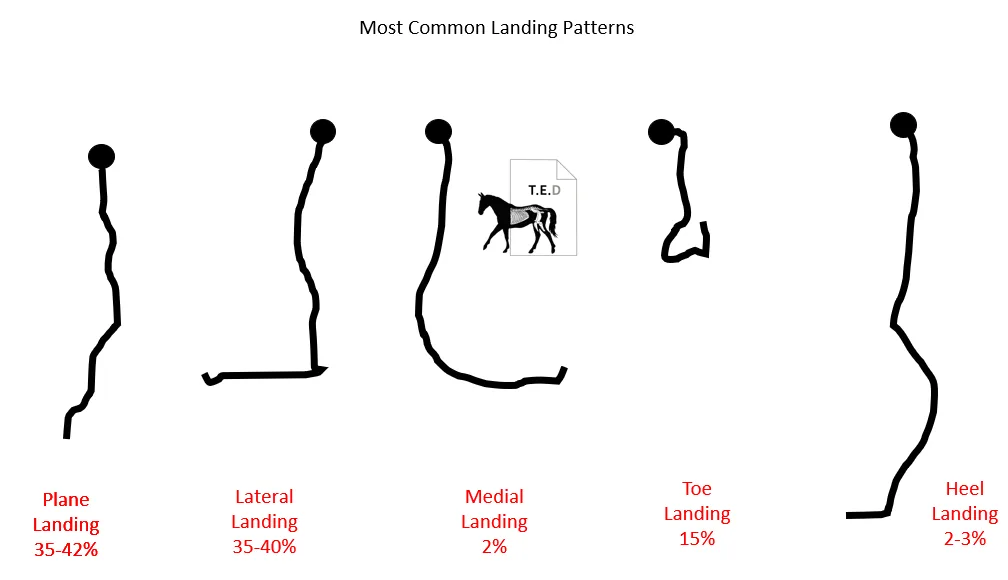

What’s important to note is that there are different CoP traces for the individual horse, controlled by proprioception received from the hoof, central movement patterns, physiology, and, of course, conformation. The most common CoP traces and their landings have been shown by different studies (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Compiled from various studies showing the landing patterns of different horses. Plane and lateral landings are considered normal due to their ubiquity.

Here is where we begin to recognise the limitations of the farrier regarding landings, and more so, we will start to see the danger in forcing level landings in horses with preferential lateral landings, for example. Studies have shown us that the farrier’s trim affects landings, up to a certain point, at which it can become counter-productive to force a level landing, suggesting other variables become overriding factors.

So, what affects these landing patterns?

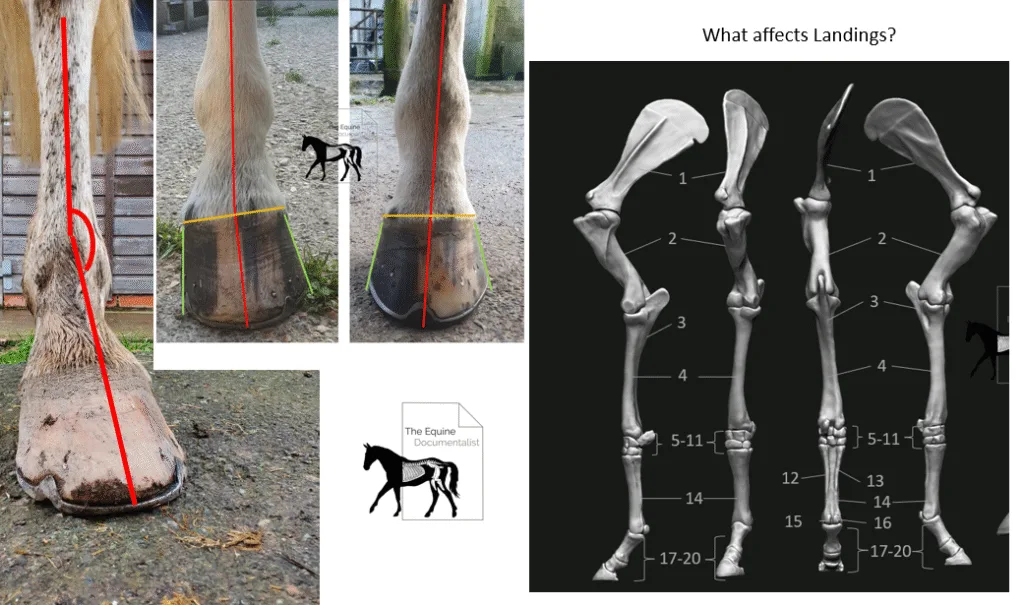

Martens et al. 2008 and other studies have stated that there was no significant difference in landings from the trim in the study. Landings were affected by the conformity of the proximal limb and, significantly, the difference between the metacarpal and pastern, the metacarpo-phalangeal angle. Medio-lateral fetlock angle (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Showing changes to the metacarpo-phalangeal angle from farriery intervention and the joints of the limb.

While farriery can have a profound effect on the metacarpo-phalangeal angle from the dorsal aspect (Figure 8) with changes in trim and shoe fit, this angle is still subject to conformation and, in some cases, posture.

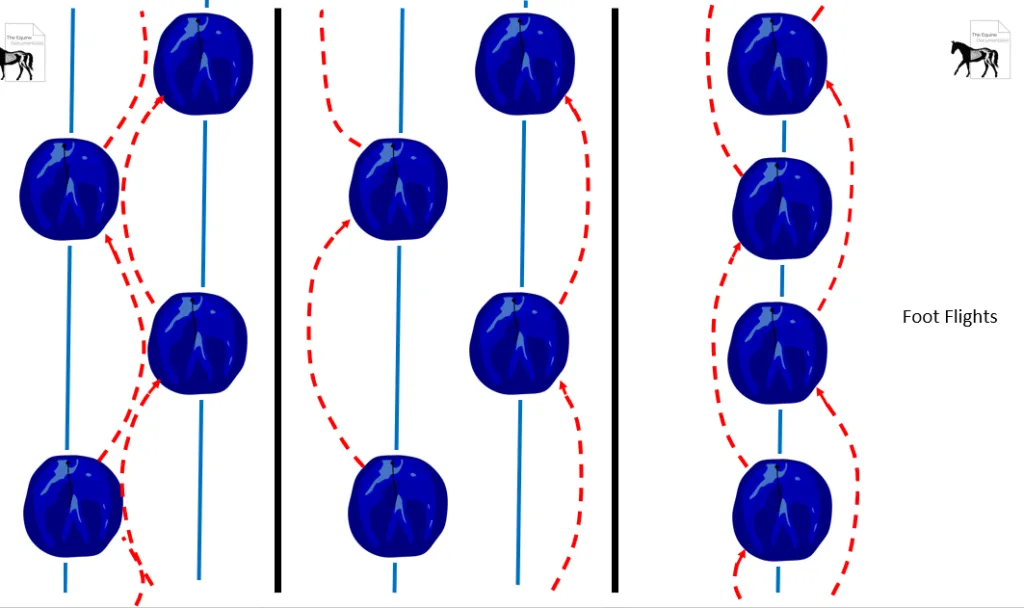

Joint angles all the way up the limb affect foot flight (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Different foot flights during the swing phase.

While farriers can have some effect on the amplitude of foot flight, it is fundamentally dictated by limb joints and muscular physiology higher in the limb. Foot flight will inevitably directly affect landing. So, while farriers can affect gross asymmetrical landings, more subtle landings are often dictated by other variables.

Vitally important to also understand is that landings are NOT what create morphological changes. These morphological changes are caused by pressure over time, creep.

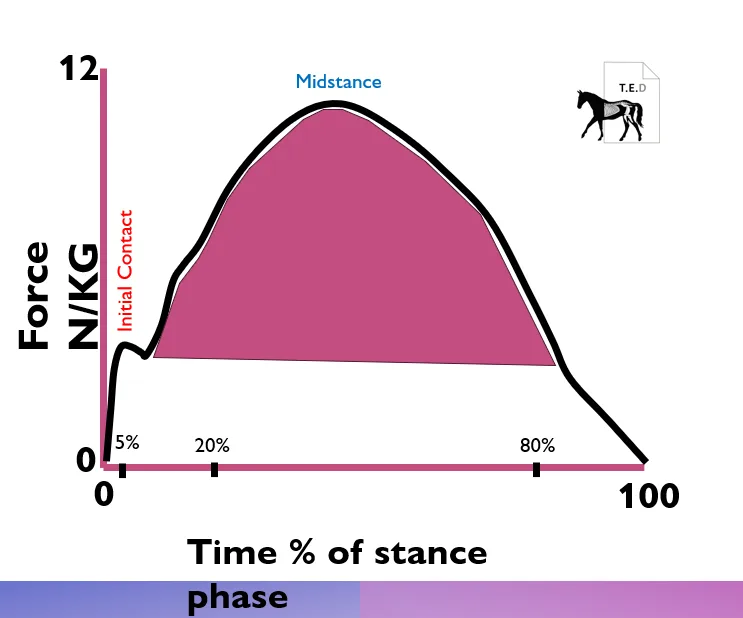

Pressure, being a product of force over area, also has a time-dependent measurement, Impulse, being force over time. Johnson (2018) studied the impulse forces acting on the hoof, citing an earlier study (Halliday et al. 2011) which defined impulse as the mathematical product of the mean force acting on the basal surface of the hoof and the duration for which the force was acting. So basically, the part of the foot that bore the most cumulative load throughout the whole stance phase. Although the foot may have a peak landing force on a particular part of the foot, it could be a different part that bears the most load through a stance phase and therefore be closer to plastic deformation strain levels. So, what becomes important to farriers when considering hoof balance is not just how the hoof lands, especially considering how this is influenced, but the rest of the area under the graph of the stance phase (Figure 10.)

Figure 10. Showing the area under the force over time graph of the stance phase associated with the loading of the hoof after landing.

We also see very clearly from this graph that while farriery focuses on landings, the forces at this point are an order of magnitude smaller than the forces being experienced by the hoof and therefore soft tissue structures therein, during midstance. The necessary shift in focus for farriers is further indicated by other research.

Rogers and Back (2007) suggested a change from flat landing at lower velocities to heel landing at higher velocities, and other studies also outlined changes in landings as gait speed increased. Johnson (2018) expanded on the different loading patterns at different gaits, citing an earlier study by Reilly (2010), which found that at walk, the hoof loaded 65% laterally, whilst at trot, the results showed a 50:50 split of force medial and lateral. Johnson (2018) found the impulses affecting the solar surface of the horse’s hoof at walk, trot, and canter were shown to be different when comparing the stance phases of the different gaits.

“The implications of this to clinical practice are considerable, as farriers tend to assess dynamic hoof balance at walk and assess soundness at trot, a lateral loading horse at walk tends to be corrected by lowering the lateral quarter of the hoof to obtain even landing at walk. The results shown here could be extrapolated to show that this may then overload the medial aspect at trot, a considerably more concussive gate.”

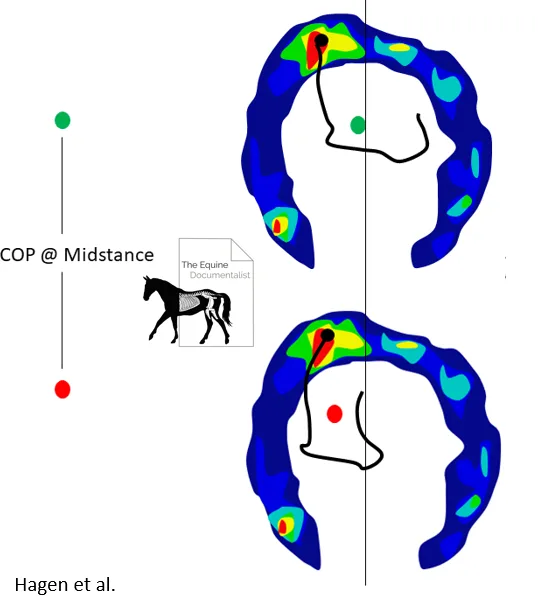

This phrase has recently been vindicated by research from Dr Hagen (Figure 11).

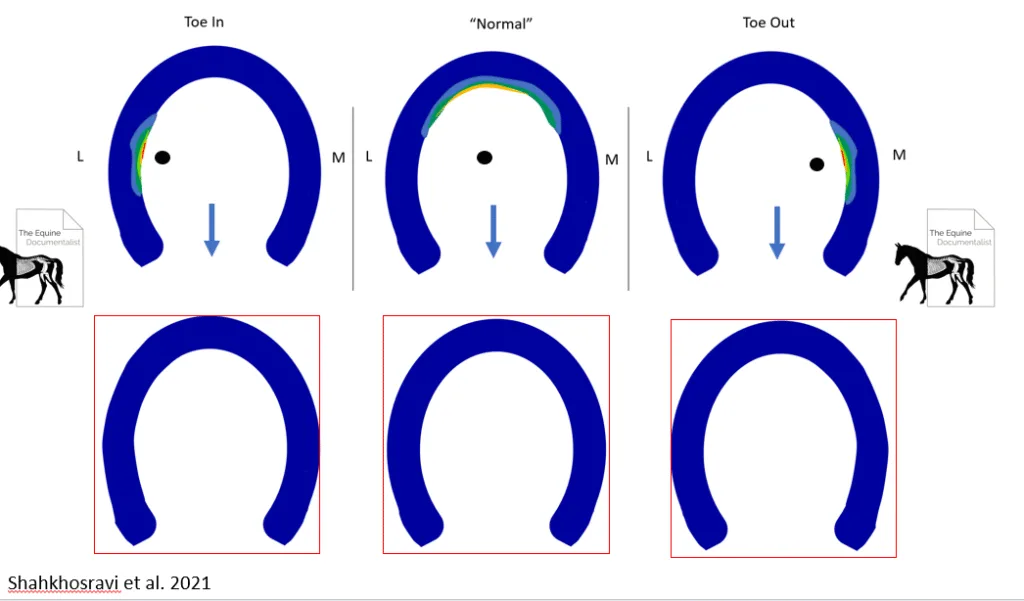

Figure 11. The CoP trace changes from a forced level landing in a horse that was showing a lateral landing preference. Figure 11 shows the findings of research from Dr Hagen. A horse that had a preferred lateral landing had a central CoP at midstance. When forced to land level, the CoP moved medially. Theoretically and logically, this focus on creating a level landing changed not only the CoP at midstance but will have affected the impulse acting on the hoof. As a result, changes in impulse to asymmetrical will inevitably cause morphological changes to the hoof over time, as shown by Shahkhosravi et al. 2021. The impulse readings of differently conformed hooves related to the areas of contraction (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Shahkhosravi et al showing the contraction of lateral/medial hoof wall according to impulse distribution.

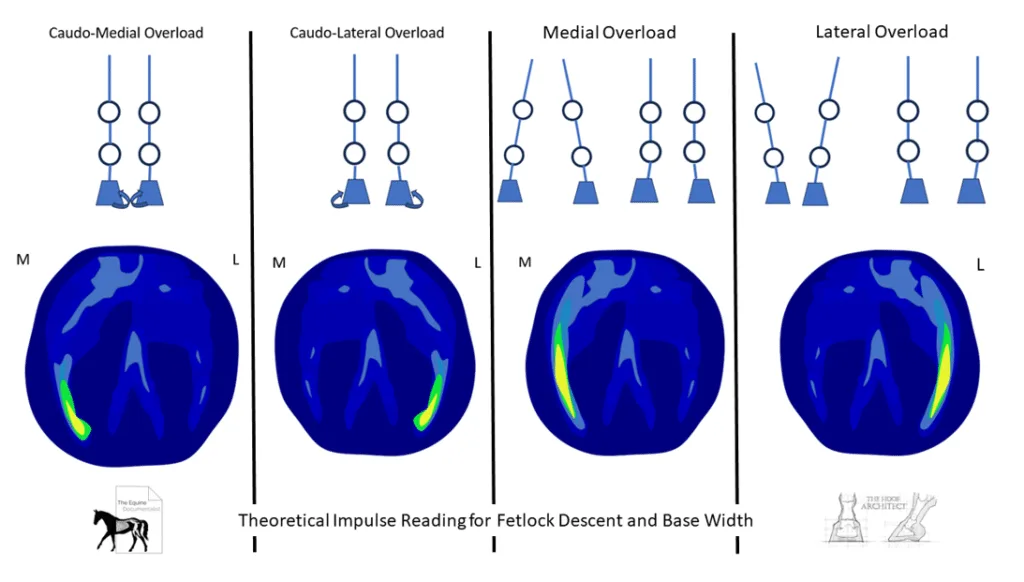

These findings were also expressed by the Hoof architect and I in a recent webinar exploring hoof morphology (Figure 13).

Figure 13. The hoof architect and I express the theoretical impulse measurements on the hoof according to different conformations.

Herein lies the fundamental issue with the historic teaching of focus on level landings!

This research calls into question widespread practices such as trimming to the long axis and medial lifts to create level landings. We will explore shortly.

Level landings DO NOT equate to evenly distributed GRFs and a centralised CoP at midstance! Or an optimal impulse! And therefore, focusing on level landings could result in the creation or exacerbation of medio-lateral hoof imbalance and issues such as shunted heels.

There is a whole other aspect to consider in this dilemma too: the interaction between the hoof, how it’s loaded, and deformable surfaces! And while displaced CoP’s from forced level landings could cause imbalanced impulses, those same changes during the loading phase will affect how the hoof sinks into deformable surfaces!!

What I am not suggesting is that landings should be ignored. What I am suggesting, backed by the logic naturally evolved from the aggregated research, is that farriery should consider morphological changes to the hoof caused by impulse. Over and above landings, once we have moved into more subtle measurements and farriery-caused changes to metacarpo-phalangeal angle have been addressed, the morphology of the hoof is reflective of the larger area under the graph.

If the horse still lands obviously asymmetrically, let’s not forget to think holistically, rather than chase a level landing, let’s also consider another variable, the horse’s physiology.

A great example of this happened in a recent clinic I did in Finland. I was presented with a horse that landed heavy on the lateral side, it had a slightly laterally offset and toe-in conformation, so some lateral landing was to be expected. However, after trimming and shoeing the horse, it continued to land heavy laterally, which moved more dorsal to the toe area. Confident in my work, I asked Tuulia Luomala, a myofascial expert, to check the horse for physiological issues higher in the myofascial chain that may be causing this landing pattern. After treatment of some myofascial restrictions in the horse’s chest and shoulder, the horse landed perfectly level!

This case is so important to understand. Traditional and blinkered farriery would have chased a level landing. Removed the shoe and removed the lateral toe height to gain a level landing, without considering two things. The morphological implication due to changes in impulse as a result, and the fact that landings are affected just as much by the horse’s physiology as the foot. What would have been the physiological implications of forcing a level landing when the landing was in essence compensatory, or rather a symptom of other issues?!

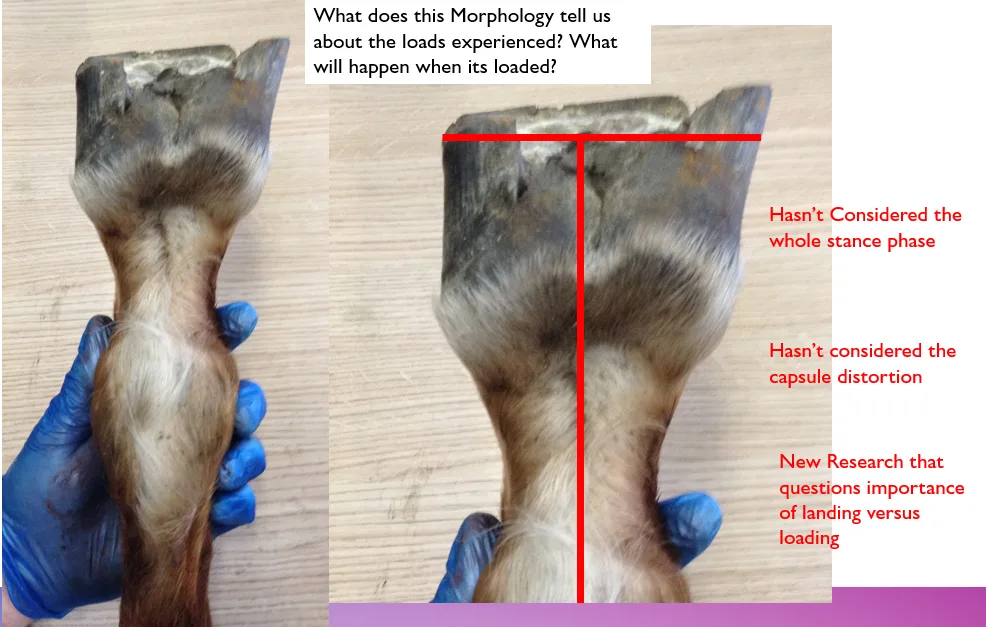

Understanding all these findings fundamentally undermines the outdated teachings on creating medio-lateral balance. Specifically trimming to the long axis. Here is an example.

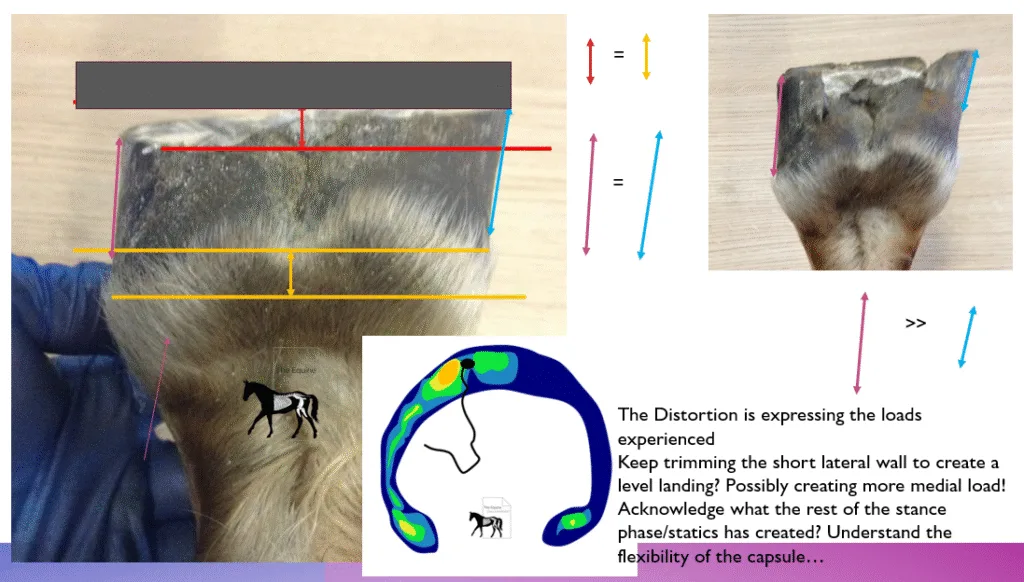

When looking at this hoof, traditional teaching would trim to the long axis, represented by the red T. But what does the morphology tell us about the forces experienced by this hoof? Does trimming to the long axis understand and address the forces of the whole stance phase? Has this trim considered the capsule distortion and the fact that the medial wall is twice as long as the lateral wall and shunted, despite the lateral wall being “higher”?

If we look at this hoof with the understanding of impulse and how this affects morphology and causes the contraction and shunting seen, a different trim is indicated when we also consider the soft tissue characteristic of the back of the hoof.

This trimming method, based on F-Balance, a trim researched and published in Germany, considers the morphological changes and understands the loads during the stance phase. It allows displaced structures to relax back into place while still creating a level landing to the eye (See shoeing suggestion represented by the grey bar). Both wall lengths have been matched by following the functional sole, leaving a flexion gap. Both landing and loading have now been considered. We also must consider the fact that medial shunting is most probably uncomfortable for the horse; the horse does not want to land level while the medial aspect of the hoof creates discomfort.

For an in-depth understanding of the theories presented here, please watch the F-balance and understanding hoof morphology webinars. Where a deeper understanding of the twists that happen to the hoof are explored by myself and the hoof architect.

In conclusion, we identify that the widespread practice of evaluating medio-lateral hoof balance according to how the hoof lands has its limitations. While farriery can affect changes to the metacarpo-phalangeal angle and of landings purely due to uneven wall heights, this doesn’t address the whole stance phase. Landings are affected by other variables that must be considered. Conformation, posture, and physiology, such as fascial restrictions, etc. Furthermore, the practice of trimming and shoeing to force level landings is also contra-indicated when considering the whole stance phase. Firstly, at landing, there are very small forces at play when compared to the whole weight of the horse on the limb at midstance. Forcing level landings may affect impulse and the CoP at midstance, and these have direct and profound implications to hoof morphology and subsequently posture and how the hoof interacts with deformable surfaces.

Considering the aggregated research presented, while creating a level landing to the eye is still good practice, it is limited by variables outside of the farrier’s control, conformation, gait, and posture, for example. Reading the hoof to understand the concentrations of load over time, and trimming accordingly, is indicated over and above a blinkered focus on creating level landings. This is especially true when taking more subtle measurements with slow-motion cameras or other technologies such as giros or pressure mats.