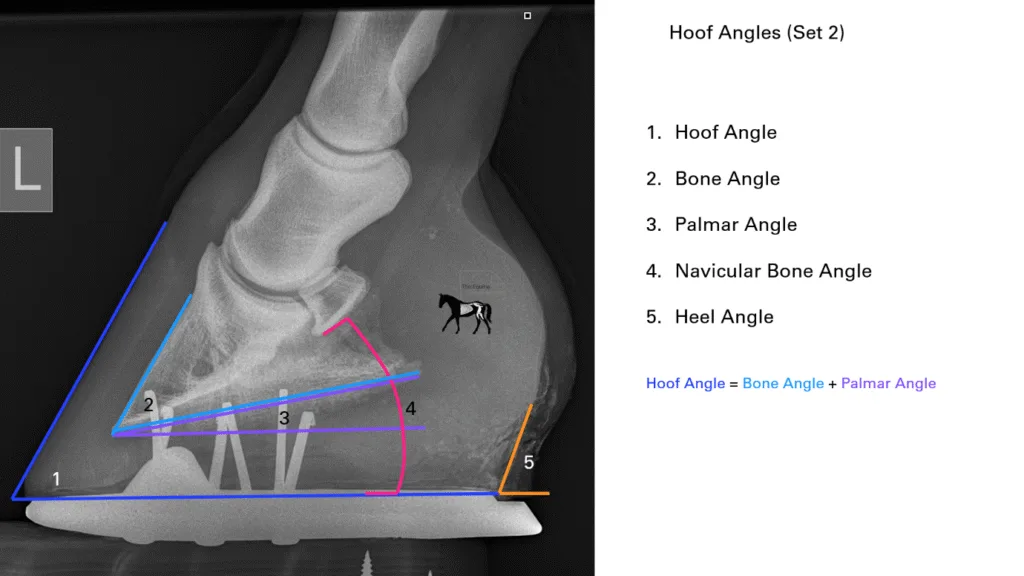

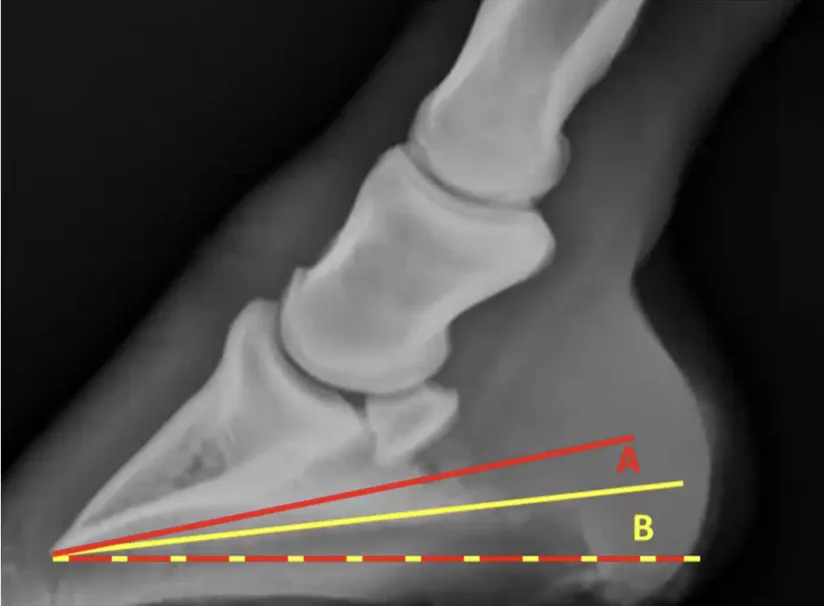

The orientation of the distal phalanx (P3, or coffin bone) within the hoof capsule is a central parameter in equine podiatry, farriery, and lameness prevention. Two key measures of this orientation are the palmar angle (PA) in the forelimbs and the plantar angle (PLA) in the hindlimbs. These terms refer to the angle formed between the solar margin of the distal phalanx and the ground surface, and they are routinely assessed radiographically (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The palmar/plantar angle is the angle made between the solar margin of the distal phalanx and the ground, seen here as angle 3. It has a correlational relationship with all the other angles.

Their clinical importance lies in their close relationship with hoof balance, biomechanics of the distal limb, and pathologies such as laminitis, navicular disease, articular arthritis, and hindlimb suspensory desmitis.

As a result, knowing the PA of a foot is of great importance in maintaining soundness in the horse. While X-rays remain the gold standard of assessing PA, they are not always affordable or practical. Authors have researched and suggested methods for understanding PA from external references to try to create more consistent monitoring of this paradigm.

Although historical consensus places “normal” values in the 3°–5° range for forelimbs and slightly higher for hindlimbs, variation exists, and in fact, recent literature has suggested hind hooves now present with lower hoof angles than front feet within subjects. PA’s importance lies not only in providing diagnostic information but also in guiding farriery interventions. Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of how deviations in these angles influence performance and pathology, highlighting the need for integrative assessment combining radiography, gait analysis, and clinical evaluation.

We have discussed ideal PA’s in depth in other articles, from the PA’s role in what the ideal dorso-palmar/plantar balance should be, how ideal PA is a factor of individual conformation, what influences it, and how what is common is not to be accepted as normal.

But the question we are answering today is, are the methods for assessing PA externally reliable?

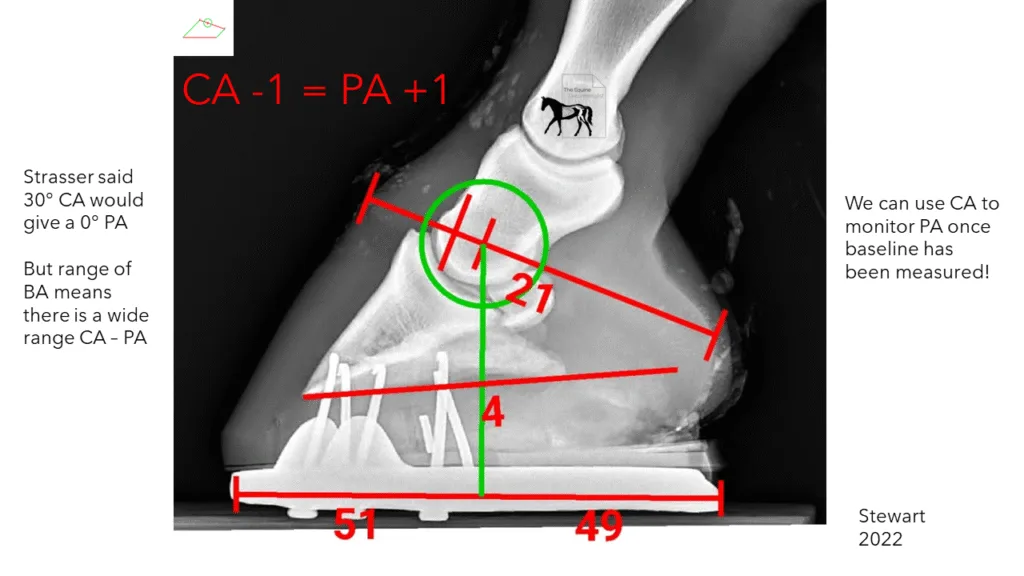

What we do know is that there is a working relationship between some of the external and internal angles of the hoof. In Figure 1, we can see how the hoof angle is made up of the bone angle + the palmar/plantar angle, influenced by the heel angle and heel-to-toe height ratios. This relationship, however, means that due to differences in the range of bone angles that exist in the horse population, unless the individual’s bone angle is known, it has been historically accepted that PA cannot be calculated from external measurements.

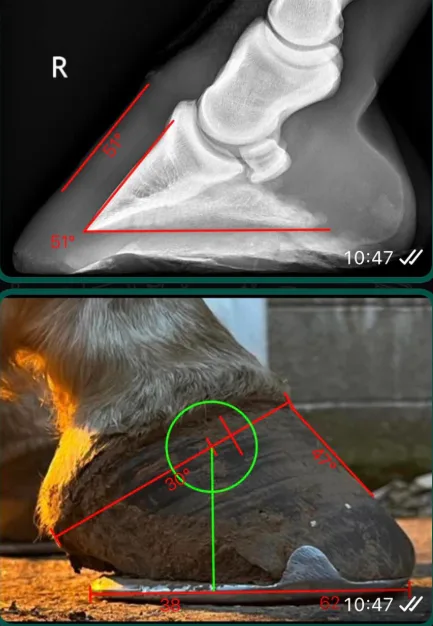

However, once we do know the horses bone angle, unless there is significant remodelling of that bone, or we have changes to the relationship between the parietal surface of the distal phalanx (P3) and the dorsal wall (from laminitis, or in severe negative palmar/plantar angles), we can monitor PA by subtracting our known bone angle from the external hoof angle (figure 2).

Figure 2. An example from the author calculating the probable PA from an external hoof angle based on a historic X-ray of the same hoof. X-ray shows a 51° bone angle; photo shows a 47° hoof angle. 47-51=-3. We can calculate a minus-3-degree plantar angle.

This clearly shows the importance of getting baseline X-rays done to enable monitoring. This example was done using HoofmApp.

But what if we don’t know the bone angle?

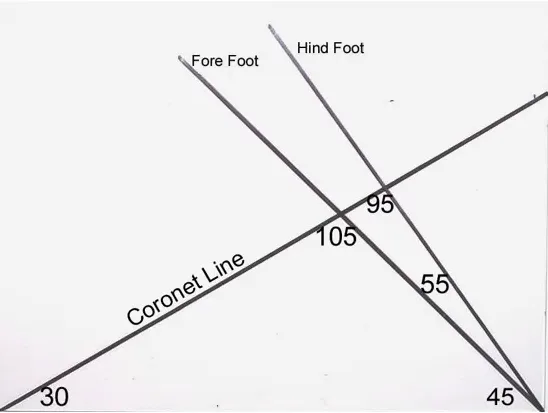

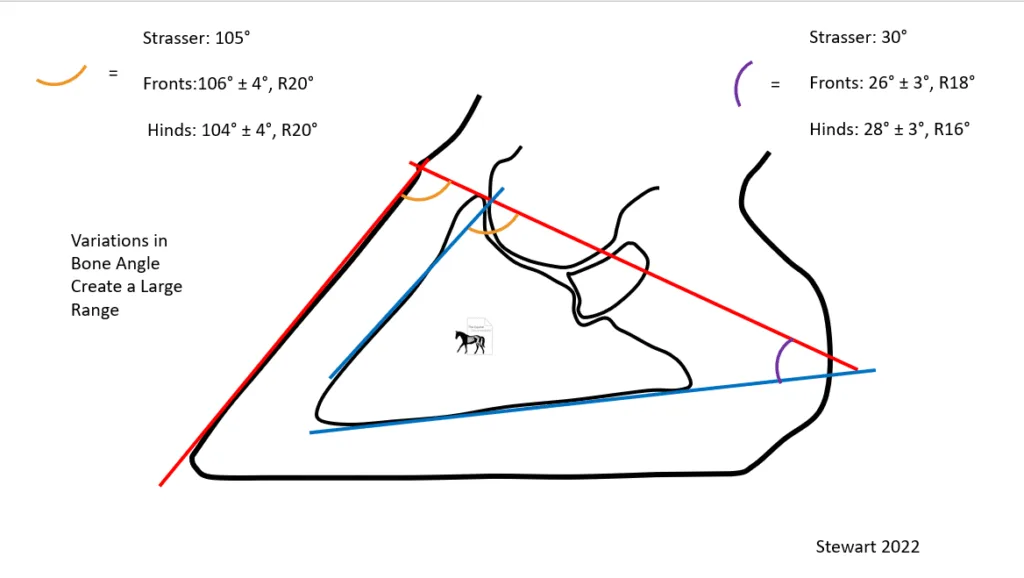

Knowing the PA without X-rays has become the holy grail, with many authors and researchersseeking formulas for calculating it from purely external measurements. In the year 2000, Dr Strasser suggested that there were some relationships between the coronet band angle and the distal border of P3 with some ideal angles of the external hoof (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Dr Strasser’s templates for correct hoof proportions. These measurements are based on creating the ideal ground parallel P3. Coronet angle should be 30 ° and the coronet to hoof angle should be 105/90 ͦ in the fronts and hinds, respectively. This is based on a bone angle of 45 ° in the front and 55 ͦ in the hind.

External and Internal Hoof Angles in Strasser’s Theory

1. The Concept of “Physiological Hoof Form”

Strasser maintains that there is a natural or ideal hoof form that optimizes blood circulation, shock absorption, and biomechanics. This form is defined in most part by the geometric relationships between external and internal hoof angles. She argues that the domestic horse’s hoof, when correctly trimmed, should mirror the natural wear patterns observed in free-ranging equids.

2. The Hoof–Coffin Bone Relationship

Strasser places heavy emphasis on the alignment between the hoof capsule (external angles) and the distal phalanx (P3, or coffin bone).

- External angle of the dorsal hoof wall should parallel the dorsal surface of P3.

- Heel angle should be continuous with the palmar processes of P3.

- Sole angle should correspond to the solar margin of P3.

Any divergence between these internal and external angles is, in Strasser’s view, pathological and a result of unnatural management practices such as shoeing, stabling, or trimming for cosmetic rather than functional purposes.

3. Ground Parallelism of P3

One of Strasser’s most cited and debated theories is that, in the physiologically healthy foot, the solar margin of P3 should be ground parallel. She suggests that the coronet angle should be 30 ° to create a ground parallel P3. Thus, the hoof capsule must be trimmed such that the coffin bone sits flat relative to the ground.

- She proposes that this alignment maximizes circulation through the corium and reduces mechanical stress.

- Deviation from this alignment is considered by Strasser to cause chronic pain and pathology, including navicular disease and laminitis.

4. Toe and Heel Angles

Strasser suggests that the toe angle should not exceed 45–50° in the forelimb and that the heel angle should match it, creating what she sees as a physiologically continuous hoof–pastern axis. She rejects higher toe angles commonly seen in farriery practice, arguing that they create abnormal stresses within the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) and navicular apparatus.

Relevant to this discussion, she suggests some angular relationships that allow us to determine PA (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Dr Strasser suggested that the coronet band angle (CA) to dorsal wall angle should be 106/104° for fronts and hinds, respectively. The CA to PA is 30°, implying that the coronet angle should be 30 ͦ to achieve ground parallelism.

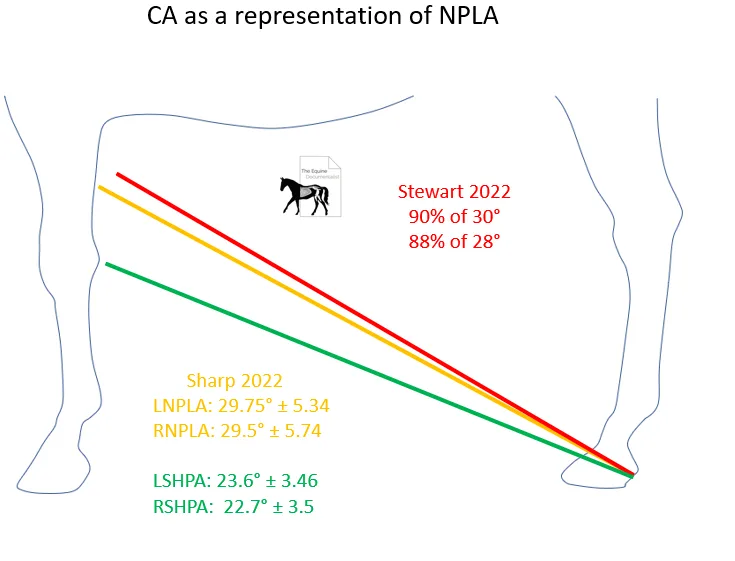

Putting aside the fact that we strongly disagree with the concept of a ground parallel pedal bone being optimal, Dr Strasser’s suggestion is that PA can be calculated by taking an angle measurement from an angle 30 ͦ from the CA (purple figure 4). This has led to the use of external templates placed on hooves to calculate internal PA using this calculation (Figure 5).

Figure 5. External template to calculate PA from Strasser’s suggested relationship. Courtesy of 3D Hoofcare.

However, these numbers were tested in a recent study (Stewart 2022) showing the average CA to PA in the front feet was 26 °, 28 ͦin the hind feet, but with a range of a huge 18 ° and 16 ͦ respectively (Figure 4). The ranges were from 17 – 35 ° in the front feet and 20-36 ͦ in the hinds.

Here in lies a hugely important principle to keep at the front of our mind as we explore other theories on calculating PA from external references. The difference between statistical equivalence, averages, ranges and clinical relevance! One could suggest that Strasser was correct within a few degrees when looking at the averages. But could be as much as 18 °out and even taking averages, a few degrees become very clinically relevant when consider every 1 ͦ decrease in PA creates 4% extra load on the DDFT!

In scientific studies, averages provide a useful summary of data, but they can obscure important variation captured by ranges. While statistical significance indicates that a difference or correlation is unlikely due to chance, it does not automatically translate into clinical significance. Wide ranges can mean that although a mean difference is statistically valid, some, or a lot, as may be the case, of individuals may experience outcomes far outside the “average,” potentially rendering the finding clinically dangerous or misleading. Think of your normal distribution bell curve. Therefore, interpreting research requires careful consideration not only of statistical relevance but also of the clinical impact of outliers and variability, ensuring that results are meaningful and safe when applied in practice.

These findings clearly show that without knowledge of the horse’s bone angle, Strasser’s method cannot and should not be used to calculate PA.

When considering PA, we must be accurate; a few degrees out could be the difference between life and death, literally!

Another relationship was suggested on the basis of the findings of the Stewart study (Figure 6).

Figure 6. A relationship suggested by Stewart (2022) to monitor PA from CA. In this example, if the CA went down to 20 °, the PA would become 5 ͦ.

Although it was shown that Strasser’s theory was incorrect and dangerous to apply in practice, Stewart (2022) implied that once the relationship between the CA and PA was known, it could be used to monitor PA over time. The theory suggests that for every degree the coronet angle decreases, the PA increases.

While in cadaver feet, this relationship holds true, we must think critically when considering in vivo. Though we understand that changes in heel-to-toe height ratios have direct and linear correlation to CA and PA, it is not just this ratio that can change PA, or indeed CA, and therefore, these other phenomena render this equation questionable in practice. Let us explore what can change the CA-PA relationship.

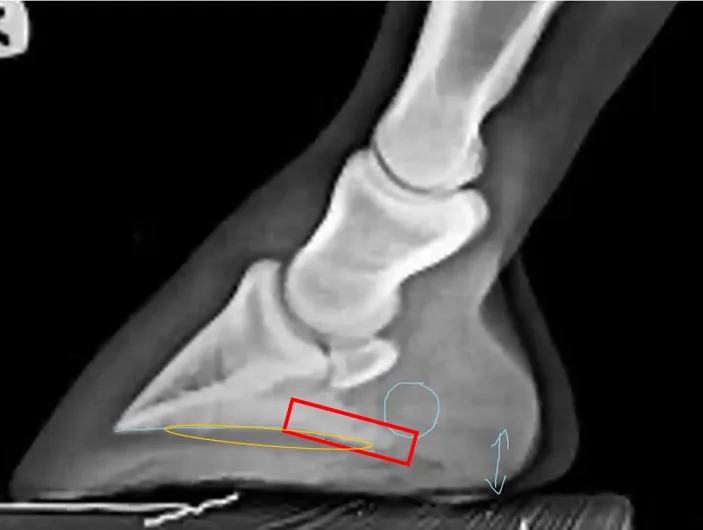

Frog engagement

When we have any degree of prolapse of the caudal hoof structure (described and discussed in depth in previous articles and webinars), this migration of the soft tissue structures of the back half of the hoof in response to gravity predisposes to negative changes to PA. Conversely, if prolapse is mitigated using pads and/or packing, this will have a direct positive effect on PA. While there will be some linear relationship with the corresponding CA maintained, further research needs to establish how much change to PA by way of these mechanisms happens, isolated from changes to CA.

Figure 7. An example of morphological changes to the soft tissues of the back of a front foot. These changes could create changes to the relationship between CA and PA as digital cushion development could change PA isolated from CA changes.

Morphological changes to CA-dorsal wall angles

As discussed by the Hoof Architect

The relationship between the CA and dorsal wall angle is also subject to morphological changes over time. This can also often be seen clearly when taking horses barefoot (Figure 8).

Figure 8 shows two feet approx. 6 months after being taken out of shoes. The new growth line shows a different angle of growth from the coronet, which could result in a different angle between the CA and the dorsal wall.

These changes could be a result of changes in load over time to the papillae of the coronet band, changing their orientation and therefore direction of tubule growth. The point of these examples is that while the relationship between CA and PA remains constant in a non-morphing hoof capsule, morphological changes can create new CA’s or PA’s isolated from each other, and therefore monitoring PA by way of CA can become unreliable over long periods of time.

There are a few studies and methods establishing measurements that imply radiographs are indicated.

Furthering the findings of Stewart, coupled with my own research, the CA angle can suggest that PA is nearing a neutral to negative plane, and radiographs should be taken (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Coronet angles can be an indication of PA nearing negative.

Historically, sighting hind coronet trajectory to the front limb has been used to imply a low plantar angle. Recently Stewart and I have suggested actual CA angles as more accurate. Stewart found that 88% of hooves with a 28° CA had negative PA and 90% or hooves with a CA over 30 °. My research confirmed these findings, showing the average CA of the horses presented with negative PA was over 29 ͦwhile after correction these went down to near 23 °. Although CA cannot give an exact PA with the additional changes in CA-PA relationships, we can use CA as an indicator that more investigation is necessary.

Another method that can be used as an indicator rather than an absolute measurement of PA is the angle of the central sulcus of the frog (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Credit Shane Westman. “The central sulcus of the frog is a pretty good indicator of the palmar angle of P3,” Westman says. “When I lay a straight edge down the central sulcus of the frog, that gives me a decent indicator that we have some trouble in that foot. It’s a very helpful tool if it’s an otherwise good-looking foot.”

Although this method can give an indication of further investigation, it shouldn’t be used as an absolute measurement, due to biological variation, and further research needs to be done to establish reliability.

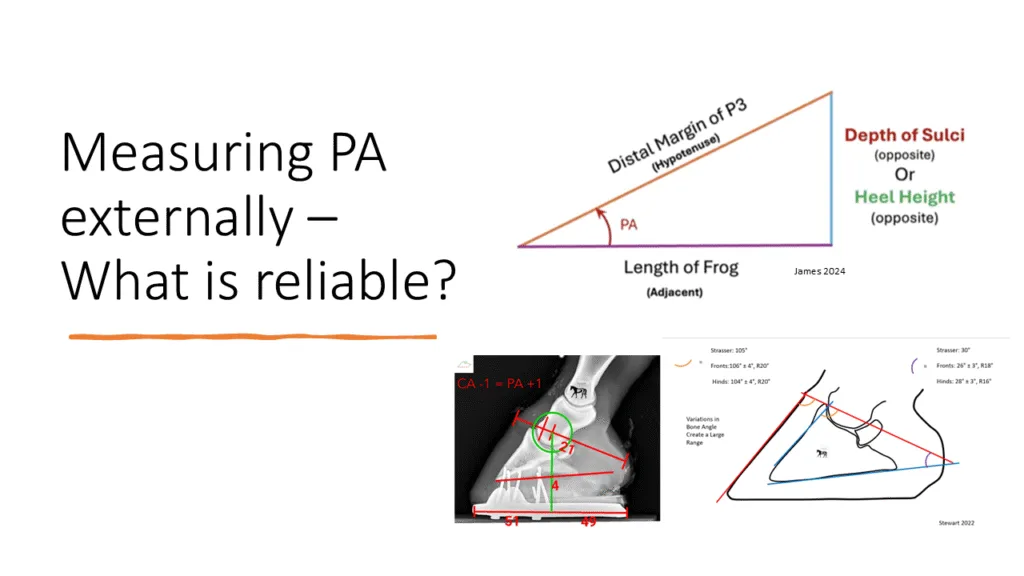

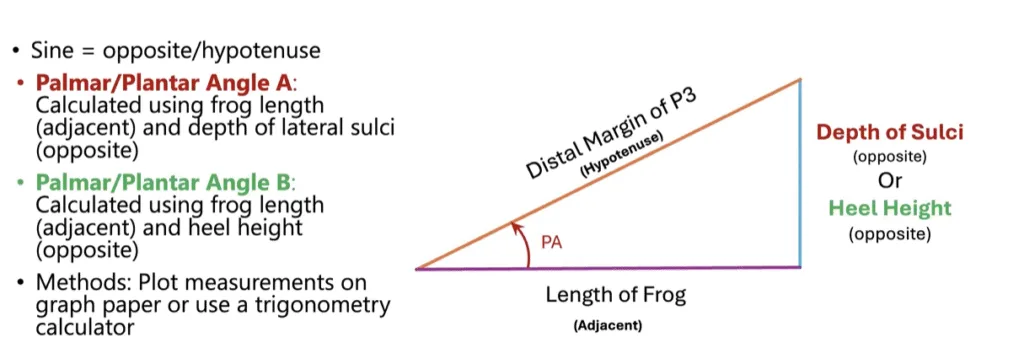

Most recently, a method has been suggested by Matt James, as seen on a webinar with the shoeing lab. The study suggested two different measurements for PA (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Credit Matt James.

James suggests that the traditional measurement of palmar angle, which follows the solar border of P3 (B)(Figure 11), can become inaccurate due to bone remodelling (Figure 12). He suggests instead the use of a measure starting at the volar arch of P3, terminating at the lower aspect of the lower palmar process.

Figure 12. Credit Matt James. Showing the discrepancy between the A and B measurements. Bone remodelling has created two angles to the solar surface of P3.

Measurement A and B become distinctly different in this image, while B would be significantly negative, A would be more toward neutral or even slightly positive. James suggests trigonometry using the length of the frog and height of the lateral sulcus gives the angle of A (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Credit Matt James. Trigonometry to work out angle A.

James’ study showed that this method was statistically reliable for working out PA angle A.

On critical evaluation of this method, there are some flaws, especially considering the concept we outlined earlier,

“In scientific studies, averages provide a useful summary of data, but they can obscure important variation captured by ranges. While statistical significance indicates that a difference or correlation is unlikely due to chance, it does not automatically translate into clinical significance. Wide ranges can mean that although a mean difference is statistically valid, some, or a lot as may be the case, of individuals may experience outcomes far outside the “average,” potentially rendering the finding clinically dangerous or misleading, think of your normal distribution bell curve. Thus, interpreting research requires careful consideration not only of statistical relevance but also of the clinical impact of outliers and variability, ensuring that results are meaningful and safe when applied in practice.”

Let’s discuss this from a critical mind.

First and foremost, we need to establish the clinical relevance of angle A. Is this the angle we should be using? James suggests that bone remodelling in this context is proliferative (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Credit Matt James. James’ theory suggests the area in red is new bone growth due to loading over time leading the study to suggest that PA should be taken as measurement A.

To establish the clinical relevance of measurement A and whether it should be used over measurement B, we must understand whether the red area is proliferated bone or if the orange area has been reabsorbed. It is widely understood that long periods of increased load on the distal phalanx results in osteolysis. Without historical radiographs of this horse, it becomes unclear as to whether measurement A versus measurement B is actually an indication of the amount of bone loss in the orange area. This becomes a fundamental question regarding the clinical relevance of measurement A, it is only the more correct measurement if the red area is proliferation! If it is in fact the case that the orange area has been resorbed, then measurement A becomes a Fallacy. Whether the trigonometry works becomes clinically irrelevant in the context of negative palmar angles. Whether it holds relevance in other contexts is to be researched.

The other consideration is that in my experience treating many hundreds of negative plantar angles, every one of them had collateral grooves. I’m not sure I can ever remember seeing inverted collateral grooves, which would be required for the trigonometry presented to indicate a negative palmar/plantar angle. The theory presented all but renders negative palmar/plantar angles impossible. Some questions need to be answered.

Do all radiographs that show negative palmar/plantar angles show two angles to the solar surface of P3? Can you ever have a negative PA using trigonometry? Can you get a negative PA when using measurement A? How negative would it have to be using measurement B to do so?

These questions need researching before this method can be utilised in practice and measurement A can be accepted as the correct PA.

It becomes clear that this study should be taken cautiously when considering applying to practice; however, it could be another method of indicating when further diagnostics should be employed.

Considering the methods we have outlined in this article, one method presents a reliable measure of PA externally over long periods of time. Get an X-ray done, measure the bone angle, and use the equation Hoof angle = Bone angle + palmar angle.

Oh, and use HoofmApp to consistently monitor the relationships discussed and this relationship in particular. Be proactive! Know your angles.